Securitization has reshaped modern finance by converting illiquid obligations into tradable securities. This mechanism not only unlocks liquidity but also redistributes risk across global capital markets.

By transforming loans into marketable bonds, securitization enables lenders to replenish capital and investors to access tailored exposures—fueling economic growth.

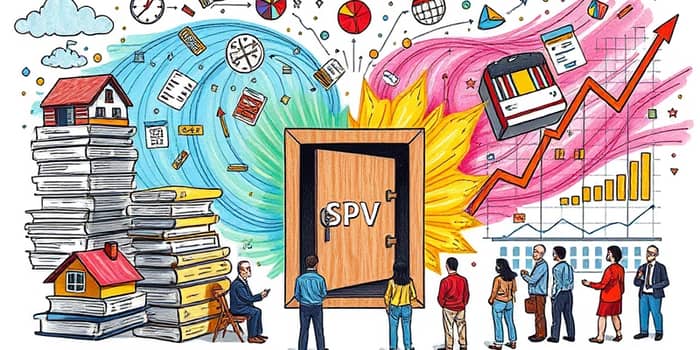

At its core, securitization involves pooling illiquid assets such as residential mortgages, auto loans, or credit card receivables into a bankruptcy-remote entity, commonly called a special purpose vehicle (SPV). The SPV acquires these assets from the originator (e.g., a bank) and issues new securities backed by the underlying cash flows.

The essential steps include:

Through this chain, the originator replaces future repayment uncertainties with immediate liquidity and servicing fees, while investors obtain new fixed-income products.

Several parties collaborate to bring a securitization to market:

The SPV’s structure protects assets from the originator’s financial distress, while tranching allocates credit risk: senior slices enjoy priority payments at lower yields, and junior slices absorb initial losses with higher potential returns.

Securitization drives value across the financial ecosystem:

By enabling match funding, lenders align asset durations with investor liabilities. This shift from deposit-based lending to fee-driven models strengthens financial intermediation.

Post-2008 reforms and the looming Basel III Endgame have introduced stricter capital rules for securitizations. Higher risk weights aim to curb excessive risk transfer but may inadvertently raise consumer borrowing costs.

These changes—such as the p-factor doubling from 0.5 to 1—alter the economics of securitization, making senior tranches costlier and potentially skewing risk-taking toward lower-rated slices.

While securitization transfers default and interest-rate risk, it also introduces complex interdependencies. Key concerns include:

Effective mitigation relies on stringent due diligence, transparent disclosure, and prudent tranche design—ensuring that higher-rated slices truly reflect robust credit buffers.

The 2007–08 housing bust demonstrated the dangers of opaque securitizations. Massive defaults in subprime mortgages overwhelmed junior tranches and triggered cascading losses in senior securities once assumed safe.

Auto loan securitizations fared differently, with collateral performance remaining stronger despite economic downturns—highlighting the importance of asset type and underwriting standards.

The securitization market stands at a crossroads. On one hand, it remains pivotal for credit expansion and risk distribution. On the other, evolving regulations like Basel III Endgame may reshape its viability in certain regions.

Striking the right balance between innovation and safeguard demands collaboration among regulators, originators, and investors. Enhanced transparency, smart tranche structuring, and proportional capital charges will help maintain securitization as a force for economic dynamism without repeating past mistakes.

Ultimately, well-designed securitizations can continue to unlock capital, broaden investor access, and foster sustainable credit growth—fueling the next chapter of global financial resilience.

References